The Box I Found (a.k.a. Writing to Remember)

August. It was our last day at Windblown Hill, the farm house where Dad grew up, and it was time to pack. The girls were downstairs with our nanny while I was tucked away in the home’s master bedroom, Mimi and Pa’s old room. I started to organize my things, our things. I stood in the big closet, a space overrun with old clothes and stacked boxes and accumulated diapers and unopened pool toys. It was when I was folding my t-shirts that I noticed that an entire wall of the closet was more closets, hidden away. I opened them.

August. It was our last day at Windblown Hill, the farm house where Dad grew up, and it was time to pack. The girls were downstairs with our nanny while I was tucked away in the home’s master bedroom, Mimi and Pa’s old room. I started to organize my things, our things. I stood in the big closet, a space overrun with old clothes and stacked boxes and accumulated diapers and unopened pool toys. It was when I was folding my t-shirts that I noticed that an entire wall of the closet was more closets, hidden away. I opened them.

There were shelves. Shelves labeled with names of people and places I recognized, labels written in what I imagine was my grandmother’s handwriting. Odd that I hadn’t seen or noticed her shaky scrawl before.

There were folders of bank documents, and old Christmas cards. There were boxes of notecards and corresponding envelopes that said, in red engraving, Windblown Hill. It was in the last cabinet I opened that I saw the green box labeled Strachan.

Dad.

I pulled it out. Opened it right there on the soft carpeting of the cluttered closet. I began to pore over its contents. I found Dad’s birth certificate; learned things I never knew – that he was born in the city of Chicago, that he was 7lb14oz, that he arrived in the world at 2:13am. I also found his acceptance to prep school, many report cards, endless newspaper clippings from his football days at Hotchkiss and then Yale. But it was the letters that got me. Letters Dad wrote when he was away at boarding school, letters penned in a more juvenile and legible version of the handwriting he’d come to have many years later. Letters to his parents, his family, his beloved dog Si.

I sat there and I read each one. These letters were full of standard-issue updates about studies and football. It turns out that Dad struggled a bit academically and would warn his parents from time to time that he might fail math or French. His letters were full of clues to the boy I of course never knew, the boy who would become my father.

He began most letters with a humorous greeting. Dear Left-Behinds. Dear Hillians. To Whom It May Concern. And he would sign many of his letters Happy Hunting! I loved how he peppered his letters with expressions – Gee! Boy! – There were details I relished. In one letter, he wrote a list of “goodies” he wanted his Ma to send. The list included the following: Cheese (like a good Wisconsin brick), little chocolates, jellied donuts, oranges. He promised to eat the latter before they spoiled. In one letter, he confessed to leaving his pajamas on a boat and asked that his parents send his other pair.

Many of his letters alluded to a theme of homesickness, of Dad having a hard time heading back to school after being home for a bit. In these letters, Dad assured his parents that he was okay, indeed “back in the swing of things.”

Some things surprised me. My Dad, the smartest man I’ve ever known, was sloppy in his spelling and his grammar was not great. I smiled when I read his apologies for his “hap-hazzard” letter writing ways, but he insisted that he had more fun this way. Dad was a serious guy, but also, somehow, all about having fun.

Some things didn’t surprise me. That there was much mention of football, of animals, of hunting. These were things I knew. Dad’s football friends were still fixtures in his life and I knew them well. Dad’s profession would become all about the animals he loved even as a boy. Though an ethicist, Dad enjoyed his hunting and his fishing. To the end, these were important aspects of his life.

But my biggest surprise? It was finding a poem that Dad wrote when he was seventeen for the Hotchkiss Lit magazine. It was called True Beauty. And here's the final stanza:

So take heed, O Cruel World, to what you always miss;

Of self-blinded leaders of Today, Beauty's what is bliss,

You can have your false-faced women;

You can have your ill-starred life.

These happy scenes are my sermon;

True Beauty is my wife.

Spending time at his house was not easy. To be so immersed in memories, in history, in the trappings of the deceased is no small existential feat. It didn’t help, or maybe it did, that I was not drinking for this visit. Historically, I would have dipped, and deeply, into the contents of that little wet bar tucked away in the library between Pa’s incredible book collection. I would have guzzled the wine in an attempt to blur it all. But this time, it was about clarity, about sharp lines, about seeing.

And I did. I did see. Despite an anxiety I felt to absorb it all, all the tiny and treasured details of a family’s life, my family's life, I saw some. I saw my own little girls running in the green grass where Dad frolicked as a boy. I saw them dance barefoot into the stables to say hello to the horses. I saw the whirl of family pictures hung up, and tucked away.

And through pictures, and letters, and words, I saw Dad. A younger version of him. The boy who would in time become the man I miss so much. So much.

And so. It was a hard visit, but hard in a good, Nietzschian way. It was a going, a grappling, a giving in. It was a seeing. A celebrating. It was beautiful in a less-than-easy, but also very true way. Maybe, just maybe, this is what Dad meant by True Beauty. Oh how I wish he were here to ask.

*

I miss him. Still. A lot. Always. What I am thankful for though is that much of the sadness about losing Dad has evolved into sweetness. A few weeks ago, after the big storm, I found myself looking out at the snow and thinking of Dad and the picture I have of him wearing his Irish hat and Barbour coat and walking our labs on my childhood block. Ultimately, I'm not sure what prompted me to post the above words today, several months after I first wrote them. I think perhaps that the more I dip into parenting my own girls, into the conscious and unconscious shaping of their childhood, the more I find myself thinking about my own past, my own childhood, about Mom and Dad and all of us girls and sundry cats and dogs, living our days, celebrating the city and the country, the humans and nature, the past and the present, of life.

Weeks before Dad died, I asked him something. He sat in an old, tattered chair in our TV room. He was weak, thin, foggy with pain. I had a hard time finding words because I knew we were in our final stretch. I asked him if I could write about him when he was gone. And he smiled. It was a pained smile, but still bright. "Yes," he said rather cheerfully. "As long as you don't trash me." Remembering this moment makes me sad, but also makes me smile. He gave me the thumbs up to do something I knew even then that I would want to do, and need to do. And I am grateful for this. For his approval. Because I'm not sure how I could have gotten here - to this day, to this very happy and grateful point in my life - without remembering him through my writing.

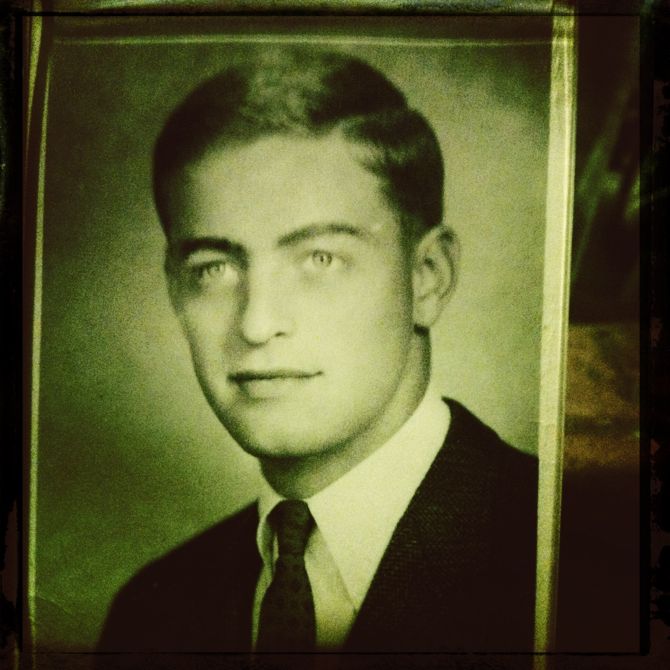

He was a handsome lad, no?

{Dad and the dogs on our wedding day in December 2004. Photo by the incomparable Philippe Cheng.}

{Dad and the dogs on our wedding day in December 2004. Photo by the incomparable Philippe Cheng.}

*

Have you lost a parent or another loved one? How have you coped with this loss?

Has writing helped you through hard things and hard times?

Have you stumbled upon things that belonged to your parents or grandparents, clues to who they were when they were young?

Do you mind reading my words about Dad? Because I am realizing more and more how important it is for me to write about him. For myself. And also for my girls who have his eyes but never had a chance to know him.